Bottom Dollar Effect

You are on a long-anticipated 10 day vacation at the beach. You’ve budgeted precisely $800 for spending money. This is the money you will use to buy souvenirs, small gifts for your nieces and nephews, or a cute pair of flip flops. It’s the last day of vacation, and you have $20 left. You want to buy some salt water taffy. It costs $18 and you are surprised at how reluctant you are to hand over your last $20 bill. It hurts a lot more than the first $20 you spent on a goofy hat on your first day of vacation, which still left you with a lavish $780 left to burn.

With $800 waiting to be spent your emotional journey might look like this…. “Oh, look at this hat, it’s perfect for the beach, I can wear it all week. A great investment! And that pepto bismol pink is perfect - it matches my suit! Only $20! I’ve got to have it!”

But with only $20 left, that salt water taffy eats up a huge percentage of your remaining budgeted money. The emotional journey might look more like this… While looking disappointingly at the last $2 of your budget in your fist and a paper bag full of taffy in the other, you might say, “I just spent $18 on salt water taffy? Salt. Water. Taffy. Do I really even like salt water taffy? I just bought it because I’m at the beach. What was I thinking?!”

That, my friend, is the Bottom Dollar Effect.

Bottom Dollar Effect - What is it?

We like to have money in our pockets and our bank accounts. When we start to run low, every dollar spent brings heightened feelings of annoyance, fear, and lack of safety. We layer those feelings onto the products and services that we are purchasing with those last few dollars in our budget.

The pleasure of the new purchase is weighed against the loss we feel with the money used to purchase it. The loss of money feels much more intense when it is a larger percentage of what we have. When we are spending our “bottom dollar,” — the last dollar in our pocket — pain feels much more pronounced than pleasure.

The way our brain thinks about spending at those moments also involves interplay with emotional dynamics like “Mental Accounting” and the “Pain of Paying.”

Let’s go over Mental Accounting first. It is useful to know that people maintain mental “accounts” when considering or managing purchases or philanthropy:

Current income – paychecks and/or the money available in checking accounts.

Current assets – homes, investments, and other less liquid assets.

Future income – bonuses, retirement income, future pay raises, and future inheritance.

You may also keep mental accounts (or actual budgeted accounts) around certain expenditures — vacation, college fund, philanthropy, food, and entertainment. The point is that in order to manage our money, we tend to organize it into various buckets.

Then there is the Pain of Paying. This is the money-specific example of loss aversion. For humans — whether it’s your bottom dollar or not — it just plain hurts to part ways with our money. It’s an example of loss aversion. Ways to reduce that pain include paying with a credit card, setting up an autopay, monthly recurring donations, and making pledges that are paid off over time. All of these options separate the decision from the drain on resources, and lower the pain in the moment.

Bottom Dollar Effect in Marketing

Studies have shown that people are significantly more likely to make discretionary spending decisions on payday or shortly after. Marketing efforts that coincide with a known payday will pay off. The small town where I grew up had two major employers — a saw mill and a paper mill. So there were set paydays that a large percentage of families counted on. I don’t know if the grocery stores and restaurants calibrated what they offered based on that knowledge, but I will bet there was an uptick in spending activity that was noticeable.

People who work on Wall Street traditionally can count on a large bonus after the end of the year. Real Estate agents get busy helping folks purchase second homes and bigger apartments. Trophy cars and high-end watches are promoted at that time of the year to the lucky bonus receivers.

Another time to promote products to consumers might be when they receive tax refunds. That check from the IRS can feel like found money.

These factors play out in the opposite direction, too. At the end of the month, when people might be feeling their budget tighten, timing discounts can help inspire people to buy, even when they feel their money is limited.

Bottom Dollar Effect in Fundraising

Know your donors. What money cycles affect them? If it’s not payday, is it the ups and downs of the stock market? When the stock market goes south, even billionaires tighten their belts. If you know and understand the way the bottom dollar effect makes your donors think about their pockets and bank account, then you’ll have more information that will help you fulfill your nonprofit’s mission, and help your donors feel really good about their support — not annoyed, put upon, or fearful — and those emotions can rub off on your organization and mission.

Once you know your donor’s money cycles, you’ll know when your requests for charitable contributions might have a greater return.

Think about Donor Advised Funds (DAFs) as a “mental account” that will come into play while donors are feeling the pain of paying. If your donors have set these up, these are funds that are set up precisely for philanthropy and nothing else. Even when donors are feeling the bottom dollar hard, if they have a DAF, there is still an opportunity to give without the pain of paying.

Pledges can also be a way to encourage your donors to make a commitment to your mission, even if they are at a bottom dollar moment. If they know an inheritance, a bonus, or another windfall is coming in the future, they can make their commitment with a pledge, and make the payment once they are past their bottom dollar stage.

Ethical Considerations

Be in partnership with your donors at all times. If they are feeling a hesitation because of a bottom dollar moment, or experiencing pain of payment, this may not be a good time to try to close a gift. And it may leave a bad taste in the donor's mouth for years to come, and pressuring is never a good fundraising tactic.

Circle back to the mission and the reason why the organization exists, the community it serves, and the way it is changing the world.

Leave space for your donors. Money brings up all kinds of unexpected emotions. Be available and let them know that they can come back when they are ready to make an investment in your work.

Bandwagon Effect

If you’ve ever managed a fundraising gala, you know how important it is to state the dress code on the invitation. Party Attire, Business Attire, or Black Tie.

While every year there is increasingly more gray area for what is “acceptable,” leaving much more opportunity for people to express themselves through their dress, you will still likely have donors reaching out to ask for an explanation of “party attire” or to ask “what do people usually wear to this event?” Why? No one wants to get it wrong.

Sure, there are people who might show up realizing they have missed the mark and can laugh it off. But most of us experience an emotion or two. From “This is so embarrassing.” to “This is really hilarious.” or even “I’m such a misfit.” Those feelings are a reaction to social proof and are what make the bandwagon such a powerful force.

The Bandwagon Effect - What is it?

When people do something primarily because other people are doing it, even if they don’t understand why, that’s the Bandwagon Effect in action. There is such a strong tendency for people to align their beliefs and behaviors with the people around them. People like to be on the winning team. They like to be in with the in-crowd.

We all experience the Bandwagon Effect every day in all kinds of mundane ways.

We patiently stand in line at the grocery store; we stand up and sing during the seventh-inning stretch; when people start to clap at a concert, we do too.

You’re out to dinner with friends and the main course plates have been cleared. The server approaches the table and asks if you’d like coffee or dessert. What do you do? I usually look around the table with a questioning gaze. I’ve somehow internalized that ordering coffee or dessert is a group decision. You’re asking everyone to linger a little longer, perhaps asking if anyone wants to share a piece of pie or an order of tiramisu. And once one person decides to have coffee, the likelihood of others at the table ordering coffee or tea is pretty high. “I will if you will!” The same is true for that second round of drinks.

It’s all about the FOMO. We are wired to want to be part of the crowd. We will adjust our behavior in order to be assured that we will be included. We will adopt a behavior, a way of thinking, a way of dressing, a way of spending our time, to increase the likelihood that we won’t be left out.

Where Did The Phrase “Jump on the Bandwagon” Come From?

Dan Rice was incredibly famous in the time before the American Civil War. His career path was varied and interesting: he started out as a circus clown, then moved on to be an animal trainer, actor, director, dancer, and finally a politician. The classic American entertainer-to-politician career trajectory.

He ran for Senate, Congress, and President of the United States, dropping out of each race. He was also one of the main models for "Uncle Sam.”

At one point, Rice campaigned for Zachary Taylor’s presidential race, and came up with the idea that Taylor use the circus bandwagon to drum up excitement. This was a mode of transportation and spectacle that Rice was very familiar with. And this is how the phrase "jump on the bandwagon" was coined.

In theory, conformity has negative connotations for Americans. We celebrate rugged individuals, mavericks, and trailblazers. We make our own decisions. We have freedom of choice. We have freedom of speech. Live free or die. But even in our nonconformity, we are looking for a version of nonconformity that other people are participating in.

Because of that, nonconformists like Dan Rice are often celebrated. And when they ask us to “jump on the bandwagon” we often become ready followers. That’s where our human tendencies override our American tendencies.

Let’s Talk About The Ways That The Bandwagon Effect Takes Hold.

The human factors that make the Bandwagon Effect so powerful are groupthink, a need to be included, and a desire to be on the winning side.

Once the majority of people in a group believe in something, it becomes increasingly hard to be the contrarian. Especially if momentum is moving away from you. Humans are wired to want to be a part of the group, and to be on the winning side (the one with the most adherents). Being the rugged individual, the maverick, the trailblazer might be something Americans all praise and admire, but most of us don’t actually want to be those things.

Do you remember that feeling as a child when you found out you didn’t get invited to a birthday party or weren’t picked for the team? The devastation? The hurt? Those are uncomfortable feelings and they stick with us. The desire for social acceptance is so strong, we’ll twist ourselves into pretzels, buy silly gadgets, dress in questionable styles, adopt outrageous hairstyles just to signal “I’m just like you” or “I’m a part of this group.”

Take a look at this old-school Candid Camera clip for an amusing and silly example of the Bandwagon Effect - Solomon Asch’s Elevator Experiment.

You think you wouldn’t turn to face toward the back of the elevator just because everyone else did for who-knows-what reason, but it’s very hard to stand your ground when you’re the only one.

Bandwagon Effect in Marketing

Social media platforms rely on the Bandwagon Effect. The only way TikTok, Instagram, Facebook, and other social media platforms function are if enough people who want to interact have joined and actively engage. Without the Bandwagon Effect, these platforms are worthless.

When you’re shopping online and you discover an “only 3 left!” warning near the purchase button, that is activating your Bandwagon Effect tendencies. It must be a great product if so many people have already purchased it. If everyone’s buying this, I want it too!

Bandwagon Effect in Fundraising

A Paddle Raise at a gala auction is one of the best examples of the Bandwagon Effect in fundraising. Pick a moment during a live auction when the energy is high - somewhere just past the middle. This is your moment to make the pitch for the mission, and then ask everyone to give. Start with a high number - but a number that you KNOW you’ll have at least one commitment. Then work your way down - from $5,000, to $2,500, to $1,000, and so on.

At each level along the way, remind the attendees about the importance of supporting the mission and why. Work your way down to a contribution level that you know every single person in the room can support. At that point ask everyone who has already given to consider an additional $10. With so many paddles in the air, it’s much more likely for everyone to “jump on the bandwagon.” Not only will you raise a significant amount for your organization, but everyone in the room will feel the joy of participating in some way. The energy should be even higher as you go into the final auction items of the night.

The collection plate has long been a staple of Sunday services in the Christian church tradition. While many churches are moving away from that practice and utilizing technology and other giving methods, it is a classic way to inspire participation from everyone at the service.

Facebook fundraisers are a great example of how the Bandwagon Effect affects social media fundraising. Your friend is raising money for the local pediatric clinic to celebrate their 30th birthday. You notice that just about everyone else in your friend group has made a donation to help them achieve their goal. You are inspired by the group, and your likelihood to ignore that fundraiser is much lower. You feel a strong pull to join your friends.

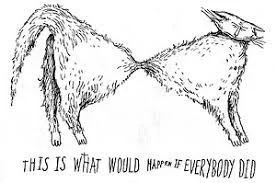

My Story: What if Everybody Did?

When I was a pre-reader, I was delighted by the book “What if Everybody Did?” by Jo Ann Stover. The illustrations are wonderfully silly and alarming. I checked it out of the library repeatedly.

The book consisted of a series of “What if…” questions and illustrations that showed the chaos that ensued if ….“everybody did.”

What if everybody “made tracks”? The illustration showed footprints all over the floor, furniture, walls and ceiling. Domestic anarchy. I loved it.

What if everybody “squeezed the cat”? The illustration showed an exasperated cat with an hourglass waistline. Poor kitty.

Jo Ann Stover’s message to children was to resist the temptation to go along with the crowd, to question the Bandwagon Effect, and beware of the chaos and damage that can result if “everybody did.”

A warning to heed - for cat squeezers and fundraisers alike. Use this powerful force to support the work of your organization, but rethink your tactics (like many churches are doing) if you sense your tactics are creating harm, shame, or embarrassment among the group of people you are trying to inspire. You do not want your donors to feel like an over-squeezed cat!

Availability Heuristic

The Availability Heuristic is a mental shortcut that describes our tendency to make decisions based on what information or examples come to mind quickly and easily. The assumption we make is that if something can be recalled easily, then it must be of high importance, it must be the best option, or it must be the correct answer. This may or may not be the truth, but it is the way our brains work.

This is the Availability Heuristic at Work

Brand recognition: Quick! Name a toothpaste, a detergent, a credit card company, a fast food chain. The likelihood that your answers are among the most advertised, most readily available products is high.

And when the brand is a common verb or noun… “I just googled it…” “Let me grab a kleenex.” or “Why don’t you just photoshop it?” then the availability heuristic is even more solidified.

Check out this list of the 30 most recognizable logos in the U.S. for more examples of inescapable brands.

Shark Attack! When you swim in the ocean do you think about sharks? The movie JAWS did a great job setting us up to be hypervigilant because of the vividness of the story. You don’t even need to have seen the movie. The ominous two-note motive on repeat is enough to evoke the fear of something dangerous lurking just under the surface. Those two notes on repeat have become a universal shorthand for danger.

So how many people are killed by a shark each year? About 10. And yet, there were six people killed by the shark in Jaws alone, just on Amity Island.

As an interesting contrast, how many people are killed in car accidents? About 38,000 every year. Millions of people get into a car on a daily basis without thinking about the risk.

If your morbid curiosity is piqued, then test out the availability heuristic by making a list of ways to die that come to mind for you, then take a look at this list of the actual most common causes of death. The most vivid examples might be things you’ve seen in horror movies or on the news. But the most common causes are less newsworthy.

The availability heuristic is a constant in marketing, check out these familiar strategies.

Be known for one thing. A good marketing tactic is to set your product up to be the most familiar solution to one specific problem. Uber, WD-40, or U-Haul are a few examples. These kinds of businesses spend a great deal of time building expertise on the issue the product or service addresses. Other tactics to build primacy for a product or service include using testimonials or before-and-after examples to illustrate results. Using a tagline or jingle on repeat to prime people to bring that product to mind quickly when it is needed also a tried-and-true technique.

Be available when most needed. Brands and products that align with the latest trends and buzzwords may get the attention that is applied to those issues. Think of Zoom. In March 2020, companies all over the world closed their offices and asked office workers to carry on from home. The Zoom brand exploded into the lives of office workers in a matter of weeks. Offsite work moved from being the exception to the dominant office work site, and Zoom was right there prepared to lead the way as the primary brand to solve the problem of effective remote meetings.

Be consistent and reliable. Some brands stick with their tag line for years, even decades. They may refine and refresh it, but consider these classics…

Melts in your mouth, not in your hands.

Just do it.

The breakfast of champions.

Think different.

Can you hear me now?

You’re in good hands.

Finger lickin’ good.

Betcha can’t eat just one.

All the news that’s fit to print.

Taste the rainbow.

How many of these can you match with their brands? While some of these have been retired, all of them live on in the minds of people all over the world.

The availability heuristic plays a role in the non-profit sector, too.

Some of the most recognizable nonprofit brands are:

World Wildlife Fund

Doctors without Borders

The Nature Conservatory

The American Red Cross

UNICEF

American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals

Habitat for Humanity

Salvation Army

Planned Parenthood

Goodwill

YMCA

United Way

These brands took years to build, and now they are internationally recognized.

Recognition comes in all sizes and shapes. If your animal shelter is the best known shelter in your local area, then your nonprofit is going to be most “available” in the minds of people in your local area when they are interested in learning more about the work of animal shelters, finding out about volunteer opportunities in the local area, and supporting your work.

On social media, there are mega-brand influencers, but there are also micro-influencers in many, many specific areas of interest. If you don’t have a nationally recognized brand, come up with ways your organization can be the best known, and the most “available” in the minds of a segment of people who would be most likely to support your mission. You want to be the go-to option for support for those who already care deeply about your cause.

Jump on the bandwagon. If local, regional, or national conversations shine a light on your subject matter, if the conversation turns to the problem that you and your colleagues are working so hard to solve, do not hesitate to get in the conversation as quickly and as loudly as possible. You want your solution to the problem to be highlighted and you want to use that opportunity to build awareness as quickly as possible. This effort to shine a light on your organization's efforts to make change within the topic at hand will have a lasting effect, likely allowing you to garner more resources and build community and recognition, and expand support for your mission, for a long time to come.

My Story: Jingles are Forever

Like most children of the 1970s, I spent a lot of time in front of the TV. There are many, many jingles I remember from 70s commercials, long retired now, but they will live on embedded in my brain until the day I die. These are brand I will never forget. Here are a few. Enjoy, but be careful… jingles are forever!

My bologna has a first name...

two-all-beef-patties-special-sauce-lettuce-cheese-pickles-onions-on-a-sesame-seed-bun

Wouldn't you like to be a Pepper, too?

And, finally, a PNW classic - not a jingle really, but one of several unforgettable Rainier Beer commercials from that era.

And if you want to go down a wacky Rainier Beer advertising rabbit hole, check out this article.

Anchoring

You need to buy a new pair of jeans, and you’re hoping you can find something “for a reasonable price.” You don’t have a specific dollar amount in mind, maybe it’s been a while since you’ve shopped for jeans.

As you start shopping, you see a pair of jeans on display in the designer section, the price tag says $500. “Wow, that's a LOT for a pair of jeans!” you think. As you look for your regular-people jeans, you end up gathering options to try on with price tags of $150, $200, and $250. Never in your life have you spent more than $80 for a pair of jeans, but now, for some reason, you’re ready to get out the credit card because $250 seems reasonable. That’s half of $500—a real bargain! That first pair of designer jeans is hanging out in your brain convincing you that jeans SHOULD cost close to $500, so $250 seems all the more reasonable.

The next day, you walk into a thrift store looking for a cute vintage skirt. You see one you like displayed by the front door for $5. It’s not your size, but you keep looking through the racks, and when you find something else you like for $25 in your size, you feel very disappointed. It’s SO EXPENSIVE! Now that $5 skirt has taken over your brain and everything else seems to be priced so outrageously.

This is the anchoring bias at work....

The anchoring bias is the tendency to rely very heavily on the first piece of information we get while in the process of making a decision. Everything else gets interpreted off of the “anchor.” We make all subsequent decisions in relation to this first piece of information and our adjustments away from the anchor are generally perceived as inadequate. Far more than we realize, that anchor has a strong pull on us. It doesn’t allow us to adjust away from it.

Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman ran a study where they asked high school students to guess the answers to mathematical equations. A group of students were given five seconds to estimate the answer to the equation:

8 x 7 x 6 x 5 x 4 x 3 x 2 x 1

Another group was given the same equation, with five seconds to answer, but in reverse:

1 x 2 x 3 x 4 x 5 x 6 x 7 x 8

The median estimate for the first equation was 2,250, while the median estimate for the second was 512. Now run it on your calculator. You’ll see that the correct answer is 40,320.

Here’s another even stranger study….

Dan Ariely, George Loewenstein, and Drazen Prelec set up an experiment with 55 MBA students in 2003. They presented several products (computer accessories, wine, chocolates, and books) and briefly described each. The average retail price for the items was $70, but that was not mentioned to the students.

Each student was then asked if they would buy the products for the dollar value of the last two digits of their social security number. After that, they were asked what would be the top price they would pay for the product. The students with higher social security numbers quoted a maximum that was significantly higher than the students with low social security numbers.

Students who had the highest social security numbers were willing to pay $56 on average for a wireless computer keyboard; students with the lowest social security numbers were willing to pay $16 on average.

Once you know about this bias and keep a watch out for it, you’ll see how it can influence your everyday life. It’s pretty shocking.

As fundraisers, we can use it for good, and sway philanthropists and donors to think bigger and reach for levels of support that can have a significant impact on nonprofits and their missions. It’s a useful concept to understand when thinking about goal-setting and campaign planning.

But first let’s take a look at some classic ways anchoring is deployed in marketing and sales.

Marketing Examples

Retail Product Position: Have you ever noticed how the sale racks are often in the back of the store? You often encounter high-end merchandise near the entrance. Often, those items are displayed in an eye-catching way and are highly sought after. The lower priced items can be found farther along on your journey. The first items you see—those high-end, high-margin, full-priced items set an anchor for you as you walk into the store.

Monthly vs. Annual plans: Slack’s pricing plan is just one of the many examples of how monthly and annual payment plans are communicated to consumers. The Pro Plan totals $80 per person when billed yearly, but they never state that price. The pricing is presented as $6.67 per person, per month, when billed yearly. You have to do the math to learn that you would need to pay $800 upfront to sign up your 10-person team. But you can pay $8 per person, per month, when billed monthly. That’s a first payment of $80 to get started, allowing for more flexibility and less upfront cost. All things being equal, Slack would like to lock you into a year-long contract and get your money up front. So they anchor you with the $6.67 price tag and entice you into the year-long commitment. If they told you that two options were $800 or $80, you might be more likely to opt into the monthly fee, even though it is slightly more expensive.

Original Price vs. Discount: How often do you see something on sale with the original price on display, but crossed out? Or a percentage discount prominently displayed: 50% off! The retailer is trying to anchor you to the original price, which often is believed to represent the actual value of the item. The current discount price is then weighed against the original price, and your brain is telling you you’re about to save a lot of money!

Now let’s look at some ways we can use anchoring in our solicitation and goal-setting strategies as fundraisers.

Fundraising Examples

Donation Forms: Consider ordering the levels in a high to low sequence. If the target group's range of anticipated giving is $1,000 to $10,000, list the levels at $10,000, $5,000, $2,500 and $1,000 is that order. People tend to settle toward the middle, and the $10,000 anchor will help some of them consider the $2,500 or $5,000 giving levels more seriously.

Major Gifts / Campaign Gift Solicitations: Are you asking someone for a one-time gift of $1 million? Maybe this is something they’ve never done before—for your organization or elsewhere—and it will be a stretch? After you’ve explained the transformative results the gift will have, if possible, offer that the gift can be paid out over multiple years. Four years at $250,000 sound much more palpable after anchoring the conversation with $1 million.

And after the payment period is over, and the pledge is paid, consider an annual gift solicitation of an amount just above the annual payment. Consider soliciting the donor for a $300,000 gift if the payment was $250,000. It’s possible that anchor might help them turn their campaign payment into annual support now that it is a multi-year routine.

Telefund Caller Strategy: When telefunders solicit a gift, is it best to ask for a gift at the higher end of the range that you suspect the potential donors might be willing to give. A number that is higher than you expect might even anchor them closer to a stretch gift. Asking for $1,000 first and working your way down to $500 is a lot easier than asking for $50 first and working your way up to $500.

Campaign Goal-Setting: When setting your campaign goals, be realistic with a splash of audacity. That goal’s anchor will push the fundraising team, your volunteers, and your board harder to work together to achieve more.

Goals that are too high may dishearten your team, and could even push solicitors to unethical behavior or a desire to fudge the numbers. I like to set a realistic goal, with a stretch goal. Roll out the stretch goal to the wider group of fundraisers and organizational leadership at the point when you feel it’s attainable with a little more elbow grease. Keep it to yourself if it seems unlikely. Put everything you have into achieving the stretch goal, but if you don’t make it you can still declare victory with the original goal. And if you do make the stretch goal, the win is even sweeter, since you’ve already signaled that the stretch goal is going to take every effort to get there.

Capital Campaign Estimates: Your nonprofit estimates the project cost at the outset of a capital campaign, engaging in months and maybe years of scrutiny, questioning, expert advice, and strategic planning. Finally, after every question is asked and most are answered, the Board votes to move forward with the new project. Campaign counsel and staff are hired, a feasibility study is conducted, and the fundraising campaign begins in earnest.

Board members and lead donors make their commitments. Meanwhile, the world marches on outside your thoroughly planned project, and lo and behold, the cost of the project begins to rise above the original estimate.

The donor who gave the lead gift to cover 25% of the campaign goal now only covers 10% of it, the timeline extends, the costs grow, and what was once a reasonable goal is increased by 30% or more. This scenario is all too common.

To minimize this issue, pack a generous contingency number into the goal, but also don’t forget to round up and raise money for general operations, ongoing maintenance, and staffing costs for once the project is complete. Perhaps this all-in number requires extending the timeline of the campaign. It may take more work and planning to get a Board comfortable with a realistic number at the beginning of the process, but also trying to encourage a Board to move up from their anchor number (the original campaign goal) once you are well on your way can be quite an emotional toll, often fraught with disappointment and blame.

My Story

Donorly has held offices at WeWork since we were a two-person staff. The opportunity to pay on a month-to-month basis and scale our contract up and down depending on the number of consultants in the New York area has given us a lot of flexibility and helped our bottom line.

Now, let me take you back to July of 2019…. I was in the process of renewing my paperwork with WeWork, the world was looking rosy, our current consulting engagements were solid, and I felt more than ever that we were on an upward trajectory. Justin, our client relationship manager, gave me the unsurprising news that the monthly fee would increase in the next month, but suggested that I could sign on for a year-long lease with our current office at a 20% discount. We’d be locked in for the year, but the savings were significant. I felt confident at the time and that 20% saving (against the anchor of the increased monthly fee) seemed like a deal that was too good to pass up.

Well, we all know the outcome of this story. I was locked in to a lease for an office we rarely used at all for several months during the pandemic. Sticking with the month-to-month lease would have saved us from a significant expense at a time when everything was unpredictable. I made what I thought was a good bet at the time, but, as we all know all too well, predicting the future is a very tricky thing.

Endowed Progress

Have you ever signed on to make a donation to a campaign and discovered that the amount pledged so far is only a small amount of the total goal? How inspired are you to give? Does it bring up feelings of embarrassment or pity? If it’s a cause you care about and feel responsible for, maybe you’ll make a gift to give it a kick start. Or maybe you’ll just sit on the sidelines and wait to see if others step up.

What about when you check in on a campaign and 75% of the goal has already been raised? Do you feel like cheering them on and jumping in to help? It’s close to the finish line, so maybe you feel more of a desire to be a part of a winning team.

Every fundraiser and every donor is familiar with the campaign thermometer. The “temperature” rises as the campaign gets closer and closer to the goal, and your enthusiasm tends to rise right along with it. That’s endowed progress working its magic on your brain and your emotions.

What is this powerful force?

The endowed progress effect happens when a certain amount of progress toward a goal is achieved. Marketers can create the sensation of endowed progress for their customers by jump starting their progress toward a goal, either as a gift, like free tokens or points in a game, or by making early progress very easy to obtain.

Marketing and loyalty program experts Joseph C. Nunes and Xavier Dreze created a research project that tested different strategies for loyalty card offers at a car wash. They created two different cards: (1) a card that required 8 purchases for a free car wash, and (2) a card that required 10 purchases for a free car wash. The recipients of the 10-purchase card were given two stamps on their loyalty card to start them off. So, in essence, each group had to do exactly the same thing: purchase eight car washes to get the free car wash.

Here’s what happened. After nine months, 34% of the people with the 10-stamp card redeemed their cards. But only 19% of the 8-stamp card holders redeemed theirs.

Both groups needed to buy eight car washes to get the free car wash, so why did the 10-stamp card have a higher redemption rate? Those who were given the two “free” stamps on their loyalty cards were instilled with the sensation of a head start, and in turn, felt more motivated to complete the card. Those two stamps made them believe they were already 20% toward completing the goal, while the 8-purchase cardholders felt like they were starting from zero.

Why does my brain do this!?

There are a few reasons why your brain reacts this way.

The Zeigarnik Effect, named after Lithuanian psychologist Bluma Zeigarnik, is the tendency to think about uncompleted tasks more than completed tasks. People who are highly motivated by a “need for achievement” may experience this much more strongly than others, but we are all nagged to some extent by unfinished tasks and unsettled by loose ends.

Task Tension is that positive feeling that exists when there's work to be done. This may include a sense of enthusiasm, the thrill of impending accomplishment, the satisfaction of checking tasks off your list, or a sense of eagerness around discovery and overcoming challenges.

Goal Gradient Effect is what happens when we get closer to achieving a reward or completing a goal. The closer we get, the more effort toward completion is accelerated and intensified. We are motivated by how much is left to do, rather than how far we’ve come. From speeding up as you get closer to the finish line to staying late at work to put the final touches on that budget, the tantalizing prospect of finishing has a significant impact on effort and desire.

How does endowed progress play out in marketing tactics?

Punch cards or loyalty cards are a classic example. If you receive a “Buy 10 coffees, get one free!” punch card with a couple of starter punches, then your coffee shop has set endowed progress into action, and you’ll be redeeming that card for your free coffee in no time.

Points, stars, and prizes are different versions of rewards that can be used to celebrate progress along the way toward a goal. They help boost your feeling of accomplishment and keep you motivated. The project management tool Asana does this by activating celebration creatures with an animation of a unicorn, yeti or narwhal joyfully streaking across your screen once you’ve completed a random number of tasks.

Loyalty programs, like airline mileage plans, encourage you to reach a certain mileage goal each year to receive VIP perks like boarding the plane first or access to upgrades. December “mileage runs” or trips just to earn miles are a common activity among business travelers who are just a few miles shy of their VIP status.

Progress bars are frequently used to inspire clients or customers to complete a task. LinkedIn uses endowed progress to encourage users to get to their profile strength from “intermediate” to “expert.” They understand it’s a tedious task for you to complete your profile, but that progress bar does a good job of nudging you along.

What does endowed progress framing look like for fundraising?

Here are some ideas that put endowed progress into action for fundraisers.

Always set goals for your campaigns and track against them. People want to know what they are working toward, they are motivated by progress, and their desire to help you complete the goal will really kick in as you get closer to completing the goal.

Never announce a public campaign with nothing raised toward your goal. Preload that campaign thermometer with a few pre-solicited gifts, and make sure your capital campaign has a significant percentage raised (ideally over 60%) from major donors before you invite the wider community to participate.

When planning a “Raise The Paddle” fundraising moment at your gala, try starting by announcing a large gift from a board member or major donor. This will help the crowd feel like they are already well on their way to reaching the evening’s fundraising goal.

Be Ethical

Set goals that inspire but don’t burden your community. Your goals should be aspirational and exciting, while still being appropriate and achievable for your organization’s community.

Make sure you are being honest about your progress. Try not to start your campaign from zero, but make sure you’ve actually raised the money that appears on your campaign thermometer. Planning ahead with some loyal supporters is all you need to do.

My Experience

I am addicted to the Alaska Airlines mileage progress bar. I do a fair amount of coast-to-coast traveling, and I check it before and after every flight. If September comes around and I’m not sure if I’m going to earn my MVP Gold 75K status by the end of December, then I’m going to be planning another flight or two. That priority boarding and a better chance for an upgrade are lovely, but it’s really that progress bar that motivates me to earn those miles.

One year, I took a one-day trip from Seattle to San Francisco on December 30 because I was about 30 miles short of my goal. It was a really fun trip, by the way. You can do a lot in San Francisco in only one day. I’m a fan of short trips anyway, but let’s be honest, some real extra joy came from seeing my progress bar completed. That was the shortest vacation I’ve ever taken, but it was great fun. And all thanks to endowed progress.

The Mysterious Power of Social Proof

You’re walking down the street and you see a big group of people gathered looking at something, but you can’t tell what it is. How likely are you to stop and take a look? The bigger the crowd, the more likely you’ll crane your neck and see if you can figure out what’s going on.

Or maybe you’re in an office building or a public space and the fire alarm goes off. You see other people looking around, but no one stops what they are doing. After a couple of minutes, you see a group of five or six people hurriedly walking toward the exit, and you find yourself gathering your belongings and following. Everyone around you is doing the same.

Have you had a similar experience? That’s social proof at work.

Social Proof - What is it?

The concept of Social Proof was first introduced in the book Influence, the Psychology of Persuasion by Robert Cialdini in 1984. It is one of the six Principles of Persuasion he outlines in the book: Reciprocity, Commitment and Consistency, Authority, Liking, Scarcity, and Conformity (or Social Proof).

We look to others when we are unsure of the correct way to behave or the best decision to make. We also look for clues from those around us when we are unsure if an action or product is trustworthy or safe.

We are much more likely to choose conformity rather than choose our own path. Our default assumption is that others have more information than us, and that assumption encourages our conformity even more.

The principle states that we determine what is correct by finding out what other people think is correct. Importantly, the principle applies to the way we decide what constitutes correct behavior. We view an action as correct in a given situation to the degree that we see others performing it.

- Robert Cialdini

This concept is illustrated through some fascinating examples in Cialdini’s book.

He talks about a restaurant in Beijing, China that partnered with researchers to increase the purchase of certain menu items. They wanted to find a way for customers to choose them more frequently without lowering prices or altering the ingredients. They tried labeling these dishes “Specialty of the House” or “Chef’s Recommendation,” but the label that had the most impact was “Most Popular.” Those two words increased sales of each dish by an average of 13 to 20 percent.

Another example of popularity producing more popularity in Cialdini’s book is a story about Netflix. According to entertainment reporter Nicole LaPorte (2018) the company had “long prided itself on being highly secretive about things like watch-time and ratings, gleefully reveling in the fact that because Netflix doesn’t have to answer to advertisers, it doesn’t need to reveal any numbers.” But in 2018, it began to share information about its most successful offerings. The results of internal tests showed that Netflix members who were told which shows were popular made them even more popular. Taking a look at my own Netflix homepage, I see that just below “Continue Watching for Sandra,” is “Trending Now” and “Top 10 in the US Today,” which I often use as a jumping off point for my next movie or binge-watching session.

A wonderful piece of opera history, and a great example of the power of social proof, is the tradition of claquers. In this fascinating article, When Paid Applauders Ruled the Paris Opera House, Ameila Soth recounts the history of claques. These groups of opera goers applauded, cried, cheered, demanded encores, and tossed flowers, all in exchange for tickets and money, in order to sway the enthusiasm of the crowd for a singer.

The TV sitcom variation on the claque might be a laugh track. We’ve all found ourselves chuckling along without even thinking (or without even thinking it’s funny), once the laugh track prompted us.

Why is this such a powerful force in our lives?

Humans are a social species. We rely on cooperation and community to survive and thrive. We have a need to share companionship and association. We all experience a pull to conform in order to be liked and accepted by others.

Social proof is what happens when circumstances play on our desire for conformity. We seek safety in numbers and relief from ambiguity or uncertainty. We look to others for social guidance in behavior.

And when we look at the crowd and see people we believe we share something in common with, we are even more willing to take cues from that group. This is known as implicit egotism, an unconscious bias to gravitate toward others who resemble us, which activates positive, automatic associations with ourselves.

Marketing Uses of Social Proof that Everyone Will Recognize

A surprising number of our buying and giving decisions are influenced by social proof. What to wear, what to drive, where to live, what to eat - it’s hard to think of a decision in my own life that is not influenced in some way by social proof.

You will immediately recognize the way that social proof is commonly used in advertising and marketing. And there are ways that you create your own shortcuts through this tactic to make buying decisions. Here’s what it looks like…

The Expert - An expert in the industry praises the company or organization. One familiar example is the use of U.S. News and World Report’s rankings of top colleges.

The Celebrity - We’ve all seen those ads: Beyonce’s endorsement of Pepsi and Patrick Stewart and Mark Hamill’s commercials touting Uber Eats are a couple of recent examples. And every athlete seems to have a sponsorship deal—or ten.

The User - More and more, we all rely on reviews on retail sites: “I’m giving this drill 5 stars! It’s easy to use, lightweight, and powerful enough for home improvement jobs big and small. A real winner!”

The Wisdom of Your Friends - One of my husband’s favorite ways to plan for travel is to pose a question on Facebook: “We’re traveling to Memphis next month, does anyone have a recommendation for a good restaurant there?” There are always some great suggestions, and sometimes some lovely wonderful out-of-the-way surprises. [To note, one of the best restaurant suggestions we ever got was from a cab driver in Honolulu - make friends with your cab driver, and then you’ll get some REAL wisdom.]

The Wisdom of the Crowd - Remember the run on toilet paper at the onset of the pandemic? Everyone was lining up at Costco to buy 300 rolls of toilet paper, any kind of toilet paper. Lines snaked around the block just to have the opportunity to shop. Why? Because everyone else was doing it. “Maybe they know something I don’t know” is a powerful motivator.

What does Social Proof framing look like for Fundraising?

The Expert - A nonprofit Advisory Board can give your organization a stamp of approval, or serve as proof of the importance and effectiveness of the work your nonprofit does.

The Celebrity - When you honor a celebrity at a gala event, not only does it sell tickets, but it sends a message that the celebrity cares about your cause and is taking time to support and promote your mission. Donors and ticket buyers want to be near them, and be like them.

The User - Testimonials from volunteers or clients of a nonprofit can give potential donors the message that the organization is caring for the community, and the people that are helped or are closely involved with the organization are happy to endorse it.

The Wisdom of Your Friends - When your friend asks you to join them at a wine tasting event in support of their favorite cause, you might be doing it as a favor to them, and to spend time with them, but once you are there, you will be much more open to learning about the mission of the organization and consider supporting them. As fundraisers, we all know how valuable that first invitation can be in cultivating a longer-term relationship with your nonprofit.

The Wisdom of the Crowd - There are many ways to utilize the wisdom of the crowd to create comfort around and support for your organization: Donor testimonials and appreciation quotes, long and prominently placed donor lists, and messaging about how many people have already donated all help to give a new donor the assurance that they are joining a large group of knowledgeable supporters.

Be Ethical

Social proof is a powerful force. Be careful not to abuse it.

Take a photo from the best angle to enhance the crowd size of your event, but don’t Photoshop in additional people.

Recruiting doctors, artists, and educators to join your Advisory Board will give your organization the glow of their knowledge and expertise. But don’t relegate them to just a listing on your webpage for fundraising clout. Engage them in your organization, ask for their advice, and listen when they have concerns and feedback.

When your donor materials use “wisdom of the crowd” messaging, make sure your statements are accurate and authentic.

“Join us” are two of the most powerful words in fundraising. Make the most of them.

My Experience

When thinking about the ways social proof has impacted my day-to-day life, I have memories of learning how to jaywalk when I moved to New York from Seattle in the 80s, and then learning how NOT to jaywalk in Seattle when I traveled back to visit.

Any New Yorker would have a very hard time standing on the corner of Bleecker and 6th Avenue waiting for the light to change from Don’t Walk to Walk, while masses of people cross the street against the light. My first New York apartment was at that intersection and that’s where I perfected my jaywalking skills. The crowd taught me what to do, and I did it.

In Seattle (in those days anyway) no matter how little traffic there was, everyone waited for the Walk signal before crossing. And, let me tell you, once you’ve perfected the art and science of jaywalking, it’s very hard to go back. But social proof had its way with me when I visited Seattle again after living in New York. In a day or two, I’d be following the street corner crowds in Seattle, patiently waiting for the light to change.

Loss Aversion and Raising Money

How do you help your donors and prospects make the leap, give their money in support of your cause, and help them feel like they’ve gained, not lost!

In this blog, we’ll to cover the following areas:

Loss Aversion - what is it?

Why do our brains do that!?

Marketing uses of loss aversion that everyone will recognize.

How can loss aversion inform how you frame your fundraising messaging?

Be ethical! Use your knowledge of loss aversion to inform, not deceive.

LOSS AVERSION - WHAT IS IT?

We all have our own stories about the moments when “losses loom larger than gains.” Why? You are much likely to retain information about moments of loss. The time you discovered too late that a $20 bill fell out of your pocket, the sorrow your childhood self felt when the dime store beach ball floated off into the middle of the lake never to be recovered, the hurt of losing companionship of a friend who snubbed you.

Contrast this with the numerous—but indistinct and long-forgotten—$20 birthday gifts from grandma, the many other little toys you had, and all of the friends you hold dear that you can always count on to be there for you.

Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky introduced the concept of Loss Aversion in their landmark paper “Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision under Risk” in 1979. Before then, the accepted assumption was that rational decision-making based on optimization was the norm.

They studied and presented a simple idea that Kahneman referred to in his best-selling book Thinking Fast and Slow, as something that we all know on an intuitive level. “Amos and I often joked that we were engaged in studying a subject about which our grandmothers knew a great deal.”

Loss aversion is a cognitive bias.

A cognitive bias is formed as a “processing error”—it’s a mental “mistake.” The reason we process loss so deeply is because of the way our brains and bodies react to fear.

Heuristics and biases are shortcuts our brains give us for decision-making. Our lives would be a lot more tedious if every decision had to be made fresh each time, as though it was the first time. We need these shortcuts for adaptive purposes. They allow us to make decisions and react quickly in dangerous situations. The problem is that sometimes these shortcuts are based on misinformation.

WHY DO OUR BRAINS DO THAT!?

The Amygdala is the brain region that mediates emotional responses, and is often associated with processing fear. Fear is a powerful force meant to keep us safe and avoid danger—an important survival mechanism that can misfire in our modern life. Loss aversion is one of the many ways it misfires.

Fear is overpowering; it takes over in a split section to help us react to danger. It is useful wiring when we see a shark, a snake, or a truck barreling towards us in the wrong lane. We need to react quickly in those moments. But because the reaction occurs in a split second, it can make us feel ridiculous when a friend jumps out the bushes to scare us, or a harmless (and useful) little spider has us running in a panic from the laundry room.

The Striatum is the brain region that handles movement, but it’s also a relay-station for motivation. It sends signals to carry out or avoid actions based on potential reward or punishment. Our past experiences are encoded in this area, and emotions resulting from past risk-taking help us predict an outcome and make a decision based on that prediction. Sometimes this is a useful brain function, sometimes not.

There are socio-economic and cultural factors at work, too.

Loss aversion affects people differently depending on what kinds of resources or community safety net they have.

People with money, resources, high social status, and power tend to view loss differently. They are less loss averse because they know that they can weather a loss better. They may not weigh the loss so heavily or feel it as strongly.

Culture also has an impact on our reactions to loss aversion. Studies show that people who live in collectivist cultures may be less loss averse, since they were brought up knowing there is a communal safety net. However, people who live in individualist cultures (like in the United States) may be more loss averse. They are taught by their society that they are on their own if things go downhill, and that it is not only their fault, but also their problem to solve. Loss is more dangerous in that context.

MARKETING USES OF LOSS AVERSION THAT EVERYONE WILL RECOGNIZE

There are so many classic marketing strategies that are familiar to all of us; whether we know it or not, we experience them almost every day. They tap into loss aversion in order to get people to act. Let’s take a look….

“Limited-time offer!”

What the brain processes: “I don’t want to miss out - this is a great offer. I need to take advantage!”

”Only 6 left in stock!”

What the brain processes: “Only 6! Once they’re gone, that’s it. I’ll never have this chance again!”

“This opportunity disappears at midnight!”

What the brain processes: “Ugh, I only have a few hours to make a decision. OK, fine, I’ll do it!”

“We’re saving this in your online cart, but there’s only a few left—don’t miss out!”

What the brain processes: “Oh! Nooooo! I wasn’t sure I wanted them yesterday, but there’s only a few left. I better buy them!”

Countdown Clocks

What the brain processes: “Time is slipping away! I need to do something before it’s too late!”

WHAT DOES LOSS AVERSION FRAMING LOOK LIKE FOR FUNDRAISING?

These same strategies are used for fundraising messaging. After all, we are selling an opportunity to make a difference. The process is the same, but the messaging might look a little bit different. Here’s how….

“Limited-time offer!” becomes “We’re matching the first $10,000 in donations 2-to-1!”

“Only 6 left in stock!” becomes “We only have 10 more tickets available to our fundraising event, and we will sell out!”

“This opportunity disappears at midnight!” becomes “Help us meet our Giving Tuesday goal. We only have 24 hours!”

“You left these great items in your online cart, but there’s only a few left—don’t miss out!” becomes “We hope you’re still thinking about becoming a member. We have 10 membership available at a 20% discount — don’t miss out!”

And…

Countdown timers become campaign thermometers.

BE ETHICAL! USE YOUR KNOWLEDGE OF LOSS AVERSION TO INFORM, NOT DECEIVE

You might be thinking, “Hey, is this ethical? It feels kind of underhanded and manipulative.”

You are trying to change the world, and you need help. Money helps! Inspiring and encouraging people to act is a good thing. Sometimes people need a nudge. And utilizing loss aversion can be that nudge. Let’s keep a few things in mind, and you can feel good about having the knowledge of the cognitive bias of loss aversion in your fundraising tool box.

Be honest. Be truthful. Be kind.

Make sure your messaging is accurate and honest when using these tactics. Don’t be like the storefront with the “Closing soon! Everything must go!” sign that never actually closes.

Make sure your campaigns come to an end when you say they will (only 24 hours left!), and report back to your donors about what their support will do.

Be kind. Don't hesitate to return donations to people who get their loss aversion triggered, but then regret it later.

MY EXPERIENCE

I am conscious of how loss aversion works on my emotions and how my brain processes it. But I still enjoy a limited time offer. I still love giving during a challenge campaign, and I still pop in to a “going out of business” sale.

For me, it triggers the same emotions as opening a birthday gift, as discovering a new restaurant, as winning a game of Hearts. It’s a feeling of excitement and reward.

If I can make other people feel good about their giving, and encourage people to make decisions that will do good in the world, I can feel pretty great about that!